As covered in past communications, a myriad of market forces impact generic drug pricing and there are many “best practices,” depending on who you ask. Some entities have identified alternative approaches or cost limits and others have worked to maintain the status quo. This tension has led to many states taking steps to address the pricing of these medications and the success thereof may ultimately drive changes at the federal level. This article will provide context on the role of generic medications, a refresher on current pricing methodology and present some of the policy proposals that are already impacting some self-funded plans.

How Generic Pricing Works

Generic pricing is certainly important to many stakeholders, although it typically does not beat out headlines related to expensive brand drugs, rebates and the delta between the list price of a brand drug and the net price after any associated rebate. Passionate stakeholders typically approach generic drug pricing from frustrations around variability in pricing and pricing dynamics related to volume and market share.

For many plan sponsors, generic drugs can represent upwards of 90% of the total prescriptions and about 25% of the total discounted drug spend. These proportions can vary significantly based on client size and specialty utilization within a given plan. For example, smaller plans may have a few specialty medications that drive a disproportionate amount of spend and thereby make the generic cost a smaller percentage of overall drug cost.

With so much of a plan’s prescription volume being dispensed as generics, it is more likely that price volatility can result in participant disruption. Generic drug prices can vary between pharmacies if one pharmacy has a low-cost generic program, similar to the $4 generic offer Walmart introduced in 2006. Price differences occur when the plan changes PBMs, as the MAC lists utilized by the different PBMs will generate margin for the PBM on different generic products. Pricing differences can also be exposed through third-party tools like GoodRx, which can deliver lower prices at specific pharmacies for specific medications when used outside of the sponsored benefit plan.

These areas of price variability and volatility are exasperated when participants are in the deductible phase of their plan and paying the full price of the medication.

Generic medications are prevalent and typically have lower prices than the reference brand drug. Upon patent expiration, a barrier to entry is removed and additional sellers enter the market. As such, the price of a generic product decreases as additional competitors come to market. An FDA study reported that the first generic version of a drug has a price very similar to the reference brand, but the entry of the second and third generic competitors led to more substantial price decreases in excess of 50% of the brand retail price.

Manufacturers sell the majority of their products to wholesale distributors, which market drugs to pharmacies. Most of these products pass through one of three distributors which control roughly 85% to 90% of the market. These entities have greater leverage in negotiations with manufacturers of multiple-source drugs because the drug manufacturers compete to gain a distributor’s business. Thus, distributors often secure lower prices from manufacturers when purchasing generics, increasing the margin between the price at which distributors purchase and sell a product.

Chain retail pharmacies are the predominant purchasers of drugs destined for retail pharmacies. It has been reported that sales to chain customers (including chain drug stores, mass merchandisers, food stores and chain warehouses) accounted for nearly half of distributors’ sales volume. The market power of a pharmacy plays a key role in these financial relationships. Chain pharmacies that serve a greater number of patients and hold a higher market share can negotiate more favorable financial arrangements with manufacturers.

Pharmacies also exert greater leverage when negotiating for generic rather than brand-name drugs. This is mainly because plan sponsors and PBMs do not control or select the specific generic product ultimately dispensed to the participant. Pharmacies can select which product to stock from all available generic versions of a drug. As a result, pharmacies may negotiate discounts and rebates for generic products. Thus, while a drug’s list price may be a good indicator of the price pharmacies pay for brand-name products, pharmacies frequently pay below the listed value for generic products due to this leverage. The size of the retail chain or an independent pharmacy’s affiliation drives its ability to leverage price concessions.

Distributors have created group purchasing organizations to gain greater access to pharmacies and consolidate additional negotiating power with manufacturers. Distributors also partner with or administer Pharmacy Services Administrative Organizations (PSAOs), which provide administrative services on behalf of independent pharmacies or represent pharmacies in negotiations with PBMs and third-party payers. The three largest distributors, all of which are listed in the top 16 of Fortune’s 2020 list of largest companies, own three of the five largest PSAOs. In these cases, the distributors are both determining the prices at which independent pharmacies procure the drugs they dispense and also the amount they are reimbursed for those dispensed medications by the PBMs. When independent pharmacies cannot get their reimbursement to cover the cost of a particular medication, their first call should be to the distributors who negotiate both the buy and sell price on their behalf.

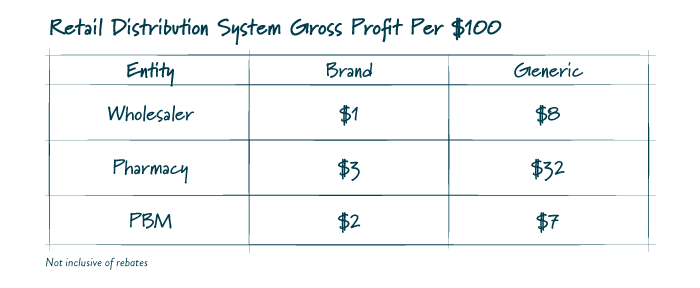

Significant gross margin is available within the supply chain, and it must be noted that proposals to reform the market seek to redistribute this margin rather than diminish it for the payor.

While exact figures are difficult to ascertain, the table below contains an estimate based on information released by the University of Southern California’s Center for Health Policy and Economics. Gross profits vary greatly between brand name and generic drugs driven in part by where each entity can gain leverage and negotiate, and also by the overall large proportion of generics as a percentage of total scripts dispensed.

FIGURE 1

Relative to generic medication pricing, the only points of leverage for plan sponsors are the composition of their retail network, plan designs impacting channel and the contract with a PBM. As such, the ability for a plan sponsor to unilaterally revamp the market paradigm is limited. Proposals seeking to regulate these limited abilities or the nature of the plan’s contract with a PBM are likely more beneficial to another member of the supply chain than the plan or its participants.

Current Pricing

Currently, a manufacturer generally sells a drug to a wholesale distributor at a list price set by the drug maker called the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC), minus discounts negotiated between the parties. The distributor then sells the product to a pharmacy at a price roughly based on the WAC. Next, PBMs reimburse retail pharmacies based on lists identifying a “Maximum Allowable Cost” (MAC) for each product. This list identifies maximum payment the PBM will pay for a particular drug. This approach theoretically provides an incentive for retail pharmacies to procure the least expensive generic version. A retail pharmacy directly or indirectly through an entity such as a PSAO has agreed to accept such pricing methodology as a condition of participating in the PBM’s network.

A PBM’s MAC lists impact how a plan sponsor, and participant, pay for drugs. Regardless of the pricing arrangement, it is important to understand there is more than one MAC list available. Under a more traditional pricing model, a PBM would reimburse pharmacies using a MAC list with lower prices and bill a plan sponsor using a MAC list with higher prices, thereby creating spread. For a pass-through arrangement, the PBM may use one set of price points for reimbursing the pharmacy and billing the client, but it does not mean that the PBM does not still utilize multiple MAC lists to optimize its book of business. There are also a host of post-transaction fees and adjustments that occur between retail pharmacies and PBMs which may not be subject to the passthrough requirements.

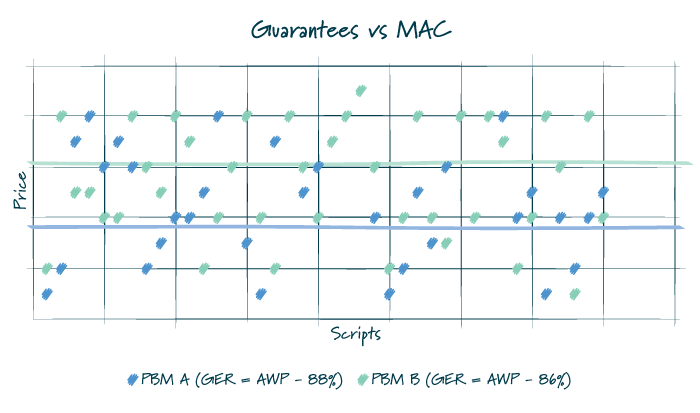

Commonly, in traditional or hybrid models, the PBM puts forth an overall average discount that must be met for all generic medications dispensed under the plan. As such, MAC lists may be manipulated throughout the year to ensure that the plan performs as it is contractually guaranteed. Given the many factors that impact utilization and drug mix, there is typically some variation between the actual performance and the guarantee. Depending on the services agreement, a plan sponsor is likely made whole for a shortfall or would have already benefited from overperformance of the guarantee.

FIGURE 2

Policy Proposals (Reimbursement Controls and NADAC Pricing Methodology)

Having navigated through the above acronyms, it is clear that generic pricing is nuanced and involves many stakeholders. As such, any seeming straightforward “transparent” solution or definitive finger pointing merits a deep review.

NADAC Benchmarking

There have been several instances of state-based proposals that require retail pharmacies be reimbursed at NADAC rates plus a dispensing fee. What is NADAC? National Average Drug Acquisition Cost, or NADAC, is a file published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that contains the results of a retail price survey that is administered by a third party. These pricing files provide state Medicaid agencies with covered outpatient drug prices by averaging survey invoice prices from retail community pharmacies across the United States.

On its face, many sponsors could believe this approach yields a greater degree of transparency, but it is important to understand some fundamentals of NADAC and these proposals. First, NADAC is an invoice price and does not include off-invoice discounts. It yields an average benchmark price that is higher than the average net acquisition cost. Second, it is important to recognize that the survey is voluntary, and many major chains and grocers do not report, leaving the sample to be comprised primarily of prices from independent pharmacies and PSAOs. In addition to reimbursement tied to the NADAC file, proposals typically also include a mandatory $8-to-$12 per prescription dispensing fee.

An analysis of generic pricing based on a large sample of self-funded plans under a well-managed PBM program identifies that NADAC pricing is similar, albeit slightly behind, MAC pricing for the top 25 generic drugs by volume. Depending on the quality of the underlying contract a plan sponsor utilizes, NADAC could very well provide a lower per-unit cost. General comparability is not a surprise as NADAC pricing is a factor that plays into many PBMs’ MAC lists, but it does not set a floor on what a retail pharmacy must be reimbursed. For many plan sponsors, especially those with an already well-managed contract, the statutorily required addition of an $8-to-$12 dispensing fee to this unit cost likely increases costs for plan sponsors.

Reimbursement Controls

Some states have successfully implemented legislation (e.g. Ark. Code Ann § 17-92-507(a)(6)) that requires PBMs to reimburse pharmacies at or above the pharmacies’ drug acquisition cost and permits a pharmacy to reverse and rebill below cost transactions if the pharmacy concludes that the MAC list rate is below the pharmacy’s acquisition cost. Such approaches have been deemed permissible under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) due to the view that this rule is within a state’s ability to regulate provider reimbursement. These types of requirements undermine the utility of MAC pricing, eliminate the incentive for pharmacies to seek to competitively purchase drugs and contribute to a plan’s greater overall pharmacy spend.

Final Thoughts

For a plan sponsor, a key question must be who is seeking to obtain a larger piece of the pie? Followed by, who will bear that cost? Regarding the latter, such cost will likely not be borne by one of the many jumbo organizations in the supply chain.

Spread is addressed by pricing model and an employer’s contract with a PBM that clearly details the operation of the underlying model. However, pricing model is not the most important indicator of the financial stewardship of the plan. The key indicator for an employer is total cost for all medications from all channels. Many pundits lose sight of this dynamic and fall into the trap of evaluating the cost of a single drug at a single retail pharmacy for a single plan sponsor. While excessive spread is never appropriate, an understanding of the total costs to the plan and its participants must complement the evaluation of any model. As such, effective plan sponsors can manage their plans without purported assistance from state legislators.

Download Article