What do shutdowns, snowballs and sages all have in common? Sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. The answer may surprise you as all three have to do with different aspects of financial health. In our country where indebtedness is the norm, the national debt in the United States just passed the $22 trillion mark1, savings are low (a recent Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System report2 found 40% of people would need to borrow or sell something to cover a $400 emergency) and herd mentality in the financial world runs rampant (The Great Recession of 2008—need I say more), the need for improving our financial health is imperative. The foundation necessary to improve your financial situation is concentrated in understanding three main aspects of personal finance: creating an emergency fund, paying off debt and understanding human thought and behavior.

If more people committed to improving their financial wellness in these three areas, the recent government shutdown may have been less stressful for those federal employees impacted, for living debt free with money in the bank allows people to weather the financial storms in life and make their money work for them. Which is where the financial sages come in. Warren Buffett and others tend to have a similar message when it comes to success with money and this message can be the steady hand when life throws the inevitable curve ball. What follows is a discussion of three pillars of financial health: emergency funds, getting out of debt and understanding human psychology, that will help to lead individuals on a path to fiscal success. Like a bad joke, financial insecurity is no laughing matter, yet there are steps you can take.

Beginning in December 2018, the budget impasse between the 115th United States Congress and the president led to the longest federal government shutdown, 35 days, in the history of our country. The previous longest shutdown was 21 days. Although technically a partial shutdown, over 800,000 workers were affected, including FBI agents, FDA food inspectors and National Park Service staff to name a few. Some federal employees worked without pay, while others were furloughed, a temporary period of time during which employees are asked not to work and are not paid during this time. As this shutdown progressed, news stories began to circulate about how many of these government employees, now without an income, would not be able to meet their living expenses. The uncertainty about the length of the shutdown caused considerable concern, especially among employees living paycheck to paycheck. Politics aside, this government shutdown, indeed all shutdowns, highlight the need for emergency funds not just for government workers—but for everyone.

Do all you can to teach, encourage and educate your employees about the value of budgets and the allocation of personal funds. For example, promote free budgeting apps (e.g., EveryDollar and Mint) and websites (e.g., Personal Capital and Buxfer). Finally, consider hiring a financial coach on an ad-hoc basis to specifically address the topic of budgeting and saving for emergencies.

An emergency fund is an amount of money set aside, the primary goal of which is to be used for emergencies and other unexpected expenses. The ideal amount of money within this fund is three to six months of expenses. Thus, if your home has monthly outlays of $3,000, then your emergency fund should fall within $9,000—$18,000. Try not to obsess over this rule of thumb. The key is to have some funds set aside for unexpected, crucial situations. Of course, what qualifies as a true emergency will vary from situation to situation; however, it is probably safe to say that purchasing tickets to a concert by your favorite band would not qualify as an emergency, while repairing your car, which is your only means of transportation to work would qualify. The challenge for many is not only finding extra money to build their emergency fund, but also having the mental fortitude not to spend it frivolously. Luckily, there are solutions for both.

The money needed to sustain an emergency fund can usually be located by creating and sticking to a budget. In many circles, the word ‘budget’ has negative connotations—saying no, doing without, a life of restrictions, etc. In a more positive sense, a budget is like giving yourself a pay raise, because now you have an awareness of where you spend money, coupled with the intention of hitting a financial goal on an ongoing basis. The strength of budgets are their ability to provide monetary guiderails, so you do not drive off the proverbial financial cliff. Seen in this light, a change in mindset about budgets can be achieved. By consistently following a strict budget, less money is wasted, allowing your emergency fund to grow. If budgets are not your style, another strategy to building your emergency fund is to begin a part-time job with the sole purpose to finance your emergency reserves. Once funded, you can quit the job.

Now that you have an emergency fund, how do you avoid spending it on non-emergency expenses? Knowing yourself is the best strategy for success. In other words, identify a location and create a plan that protects you from your spending habits. Obviously, you want access to this money (it is needed in emergencies), but it should not be easy to spend. One strategy to resist temptation is to place this money in an account separate from your everyday accounts. In other words, these funds could be located at a bank different from your commonly used checking/savings accounts, which keeps it out of awareness and limits its use.

Now that you have an emergency fund, how do you avoid spending it on non-emergency expenses? Knowing yourself is the best strategy for success. In other words, identify a location and create a plan that protects you from your spending habits. Obviously, you want access to this money (it is needed in emergencies), but it should not be easy to spend. One strategy to resist temptation is to place this money in an account separate from your everyday accounts. In other words, these funds could be located at a bank different from your commonly used checking/savings accounts, which keeps it out of awareness and limits its use.

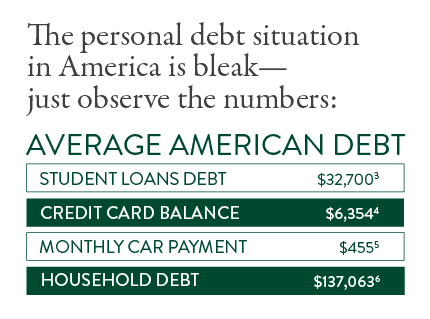

The problems with debt are multifaceted. First, debt reduces the amount of money you are free to spend, which limits choices. Second, by definition, debt moves future consumption into the present7. In other words, borrowing money today requires you to pay it back into the future, which means less money available down the road. This can be problematic for the United States—the largest consumption-based economy in the world8. Third, the presence of debt makes it difficult to retire. For these and many other reasons, we should aim to be unlike most Americans when it comes to possessing personal debt.

Continue to cultivate the budgeting mindset. Budgets rein in spending and raise awareness about consumption habits. Evidence9 continues to suggest that people who live on a budget spend less and save more – this behavior pattern is associated with reduced debt over time. In addition, consider covering or supplementing the cost of turnkey financial classes focused on getting out of debt and building wealth (e.g., Dave Ramsey’s Financial Peace University). Further, make it policy that every new staff member must, as part of the onboarding process, attend a budgeting/debt reduction class. Finally, restructure benefits to include paying off some or all an employee’s student loans over time.

So how does one get out of debt? The answer to this question has to do with the debt snowball—an approach to getting out of debt by first listing all debts from lowest to highest. Concentrate on paying off the smallest debt while making minimum payments on all other debts. Once this smallest debt is eliminated, roll that payment to the next highest debt. While not a mathematical approach to eliminating indebtedness (the order of payback is based on size of the loan, not its interest rate), the snowball approach is a psychological one. Eliminating the smallest debt allows for a quick, initial win, which is psychologically satisfying and helps build momentum and your likelihood of success. Put another way, the debt snowball is a solution for lack of progress and motivation.

The third pillar of personal finance success has its roots in the field of psychology. Simply put, psychology is the study of the human mind and behavior. Sages of the financial world understand and use human psychology to their advantage. Benjamin Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor) once said, “The investor’s chief problem—and his worst enemy—is likely to be himself. In the end, how your investments behave is much less important than how you behave.”10. Thus, triumph with your finances is predicated on keeping your emotions in check. It is about having the correct temperament, character and guts. It is about behavioral discipline.

Dave Ramsey11, a financial radio show host who specializes in helping people get out of debt and build wealth, states that personal finance is 80% behavior and 20% knowledge. The list of fiscal sages who share similar beliefs about the power of behavior is noteworthy: Warren Buffett, Jack Bogle, Charlie Munger and Shelby M.C. Davis to name a few. Well-known authors, Carl Richards and Morgan Housel, also espouse the importance of actions and temperament as important ingredients to success with money. Morgan Housel, currently a partner at The Collaborative Fund and a former columnist at The Motley Fool and The Wall Street Journal, even created a hierarchy of investor needs—similar to Maslow’s pyramid of the hierarchy of human needs found in any introduction to psychology textbook. According to Housel, investor behavior forms the base of investor needs and thus is the first ‘need’ to be mastered before anything else matters. He goes on to state, there is a, “preference for skills in a field [finance] where skills don’t matter if they aren’t matched with the right behavior.”12. With so many sages of the financial world repeating a consistent refrain, it is a wise bet they are on to something. Heed their advice about improving your chances of success with money by spending a lot more time understanding your emotional brain rather than your financial brain.

There you have it, the path to financial health is at least partially paved with shutdowns, snowballs and sages. Shutdowns serve as reminders of the importance of emergency funds, while the debt snowball represents an approach to achieve a debt-free status. Finally, sages of the investing world, past and present, continue to emphasize financial success as the process of understanding the psychology of the person each of us see in the mirror. While by no means complete, progress within these three domains will improve not only your success with money, but your relationship to it. Individuals are not alone, as employers can offer assistance to employees in the form of classes, benefits and nudges to improve the odds of success. The time is now to chart a new course with our finances—all joking aside.

Offer seminars on behavioral economics, the study about the way people make economic decisions as well as the rationality or irrationality driving these decisions13. Consider using the concept of nudges to help employees with their retirement savings. Employers are increasingly auto enrolling all employees into the employer’s retirement plan. Employees who do not wish to have retirement contributions deducted from their paycheck must consciously opt out of the plan. As you can see, being enrolled in and making retirement contributions is the easier option (it happens automatically), yet employees can opt out if they wish (this takes conscious effort, is not automatic, yet preserves choice). Taking this concept a step further, employers may consider automatically increasing employee contributions each year by a predetermined percent, with the option to opt out requiring a deliberative effort on the part of the employee. Finally, do all you can to make saving or paying automatic for your employees. Automatic savings and/or payment plans allow employees to set it and forget it, thereby reducing errors, forgetfulness or missed payments due to unexpected financial emergencies.

References

- Treasury Direct. (2019). The debt to the penny and who holds it. Retrieved from https://www.treasurydirect.gov/NP/debt/current

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2018). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2017. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2017-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201805.pdf

- Federal Reserve. (2017). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2016 – May 2017. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2017-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2016-education-debt-loans.htm

- Sullivan, B. (2018). State of credit: 2017. Retrieved from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/state-of-credit/

- Glover, L. (2018). What you can (and can’t) learn from the average car payment. Retrieved from https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/loans/auto-loans/average-monthly-car-payment/

- Sun, L. (2017). A foolish take: Here’s how much debt the average U.S. household owes. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/personalfinance/2017/11/18/a-foolish-take-heres-how-much-debt-the-average-us-household-owes/107651700/

- Mauldin, J. (2015). Excess debt is like a black hole, sucking in all the life around it. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/debt-is-like-a-black-hole-2015-2

- Vollmer, C. (2013). Consumption-based economy. Retrieved from http://jobenomicsblog.com/consumption-based-economy

- Moss, W. (2018). Strategies for budgeting and saving money. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/how-to-budget-and-save-money-in-5-easy-steps-4056838

- Davis ETFs (n.d.). Retrieved from https://davisetfs.com/investor_education/quotes#collapseDisclaimer

- Ramsey, D. (n.d.). What’s the reason for the debt snowball? Retrieved from https://www.daveramsey.com/askdave/budgeting/whats-the-reason-for-the-debt-snowball

- Housel, M. (2018). The psychology of money. Retrieved from https://www.collaborativefund.com/blog/the-psychology-of-money/

- Samson, A. (2018). The behavioral economics guide 2018. Retrieved from http://www.behavioraleconomics.com.